“Found community and purpose and a much – I was saying earlier about, you know, like – it was almost kind of a – I mean, I grew up in a time – my early days of coming out were really centered around bar culture. Like, that was all I knew of was going to bars, and it’s limiting and it’s typically not a healthy environment. I mean, there’s smoke, there’s alcohol. I mean, I had some fun for sure, but I wouldn’t say it was wholesome fun, you know, and it wasn’t – it wasn’t purposeful other than to be in a safe space. So, yeah. So, getting involved in HIV work and AIDS activism expanded my network of people. I learned about things I had inside myself that I didn’t know, that hadn’t been exercised. My own ability to be an advocate, my ability to fight for justice, to raise my voice, to find a purpose, for sure.”

On Her First Experience in a Buddy Program:

Being a buddy, my first buddy Willis was – he lived in West Philly. He had moved to San – he was young. He was maybe twenty-five or six. He was a young man. He moved away from Philly right after high school to San Francisco, where he felt he could be more liberated as a gay man. He was a Black gay man, and he – you know, his family may or may not have known he was gay. It was, you know, a story I’d heard many times but you kind of go to find another replace to start your life over – excuse me – so, I was assigned to him and I remember driving to his house in a part of Philadelphia I’d never been to because I didn’t have friends there, didn’t have family there. It was a predominantly or maybe exclusively Black neighborhood. It was a neighborhood that you know, I’d heard stories about. It was like one of those places you don’t go, and I find his house. It’s this lovely residential street, very quiet. His mother greets me. She is warm and lovely, and she says, ‘Willis is upstairs. Go head up.’ So, she just followed the stairway all the way up – followed the stairway all the way up and there’s this tiny little bedroom at the top of the stairway, kind of as far away from anybody as it could be, and there’s this tiny – you know, just wasted away guy, adorable, you know, sweet face, and just kind of was skin and bones at the time. And he was laying in a hospital bed, had a TV and really not much else in the room – some water and a straw, and you know, I just started talking with him.

Held his hand, asked if he wanted a massage and massaged him. You know, asked him about his favorite foods, so that the next time I would come I’d bring some food. And we really – you know, he didn’t live very long but we had – I visited pretty often. He told me all the stories about his life and dancing the night away in San Francisco and just – he’s animated and lovely even though his body was really failing him. At some point he had to be hospitalized and I visited him in the hospital a couple times. Brought him some food. I remember his favorite food – this is kind of funny because it tells you that I was a little bit naïve at the time. He loved fried shrimp. It was like, his favorite thing in the world. So, on one of my visits to see him in the hospital I stopped at a seafood restaurant that you know, had a good reputation and I got him a fried shrimp platter and I brought it to the hospital. He was so excited about it and he ate, you know, a few bites of it and you know, threw it all up because he was too sick to eat fried shrimp. He’s too sick to eat anything. And I was like, ‘Okay, that’s no big deal. We’ll just clean it up, you know.’ But he got to taste fried shrimp and I stayed focused on the fact that he got to taste fried shrimp.

So, that’s my first experience and I learned a lot. I became very close to his sister and his mom. It’s kind of interesting. They used to – they referred to me as their ‘white angel’ and I never really understood. I mean, I guess for them it’s possible that they never had a white person who was kind of so included in their lives. I mean, I remember I was invited to his sister’s baby shower. I would often sit and eat with the family. I think it was really new to me and I think it was really new to them. And I was a little – I was a little uncomfortable with the sort of ‘white angel’ thing because A, I definitely am not an angel, and I just didn’t like the sort of differentiating around race, but I also feel like, okay, you know, what does it mean to them to call me a white angel? It means that they really appreciate what I did and that I was there for their son and I just had to embrace that.

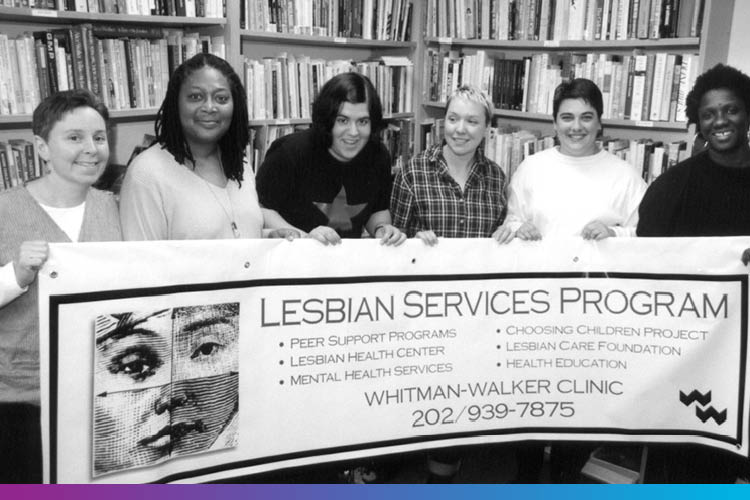

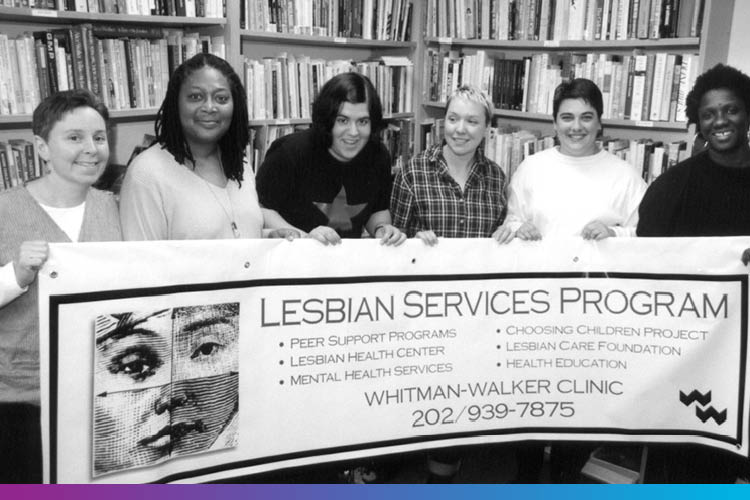

Ellen is on the far left, holding the Lesbian Services Program banner.

So, that was like a – as you can imagine, a very life-changing experience. I made a quilt for Willis for the National AIDS Memorial Quilt. That was, you know, just a very meaningful experience for me as well, so – and after Willis, I had another maybe five or six other buddies over time. I used to keep a journal and any time one of my buddies died or later, my clients when I became a case manager, I would write one page in the journal about them and capture. The sad thing is that at one point I couldn’t keep up. You know, so I had maybe eight or ten or twelve, I don’t know, entries, and then I just couldn’t keep up.”

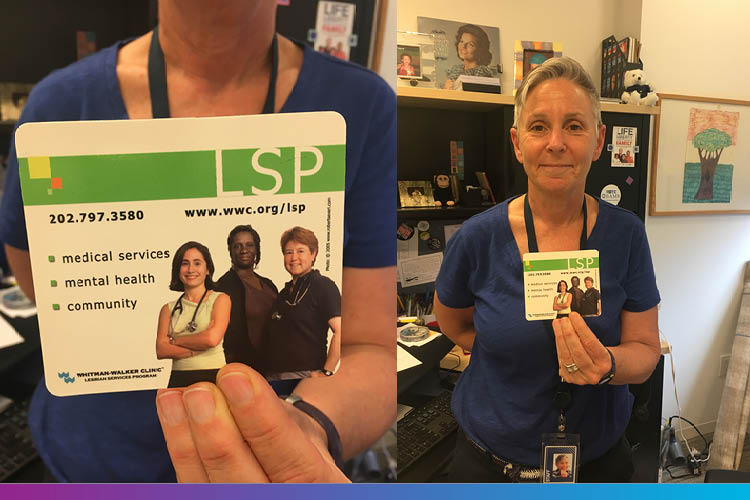

“But the real sort of, you know, passion for me was Lesbian Services and being able to kind of grow that program to – you know, to move that program into a really nice space where we could have something that really felt like a drop-in center or community center for the women’s community. We got to, I think, really do cutting-edge work to include trans guys in our system of care and our services and to try to be more accessible to women of color, women of different identities but who are part of the queer women’s diaspora, if you will. It was really just like, probably seven of the best years of my life for sure. I also became a parent during that time and what I really love about having been at Lesbian Services is that one of the programs that launched at Lesbian Services before I was a director was – I believe it was called Choosing Children and it was a program that provided support groups and some educational resources for lesbians who were interested in becoming parents. And it was still a relatively new thing, you know, back then, and as someone who was interested in becoming a parent and started to go down that path but with my partner at the time, I was able to kind of grow the programs at Lesbian Services almost to reflect what I was finding were kind of the unmet needs and opportunities for more programming.”